Preservation of Hot Super-Earths and Cold Gas Giants

Yi-Xian Chen (Tsinghua University), Ya-Ping Li (LANL), Hui Li (LANL), Douglas N. C. Lin (UCSC & Tsinghua University)

Abstract

The abundance of super-Earths suggests that they are able to be retained in natal disks around low-mass stars, whereas exoplanet’s mass distribution indicates that some cores have transformed into gas giants through runaway gas accretion at larger distance. In this work (Chen et al. 2020), we show that transition to runaway gas accretion by core may be self-impeded by an increase of the grain opacity in their envelope after they have acquired sufficient mass (typically ∼ 10M⊕) to enter a pebble-isolation phase. The accumulation of ∼mm-m size pebbles in their migration barriers enhances their local fragmentation rates. The freshly produced sub-mm grains pass through the barrier, pollute the planet's gas envelope and reduce the radiative flux in the core’s envelope. This effect efficiently suppress the transition to runaway accretion and preserve super-Earths in the stellar proximity. Beyond a few au, the transformation of more massive cores to gas giants is reachable before severe depletion of disk gas. This requirement can be satisfied either in extended disks with large scale height via orderly accretion of migrating pebbles or through the mergers of oligarchic protoplanetary embryos, and can account for the correlated occurrence of long-period gas giants and close-in super-Earths (Zhu & Wu 2018).

Presentation material of a detailed talk on this project

The General Picture

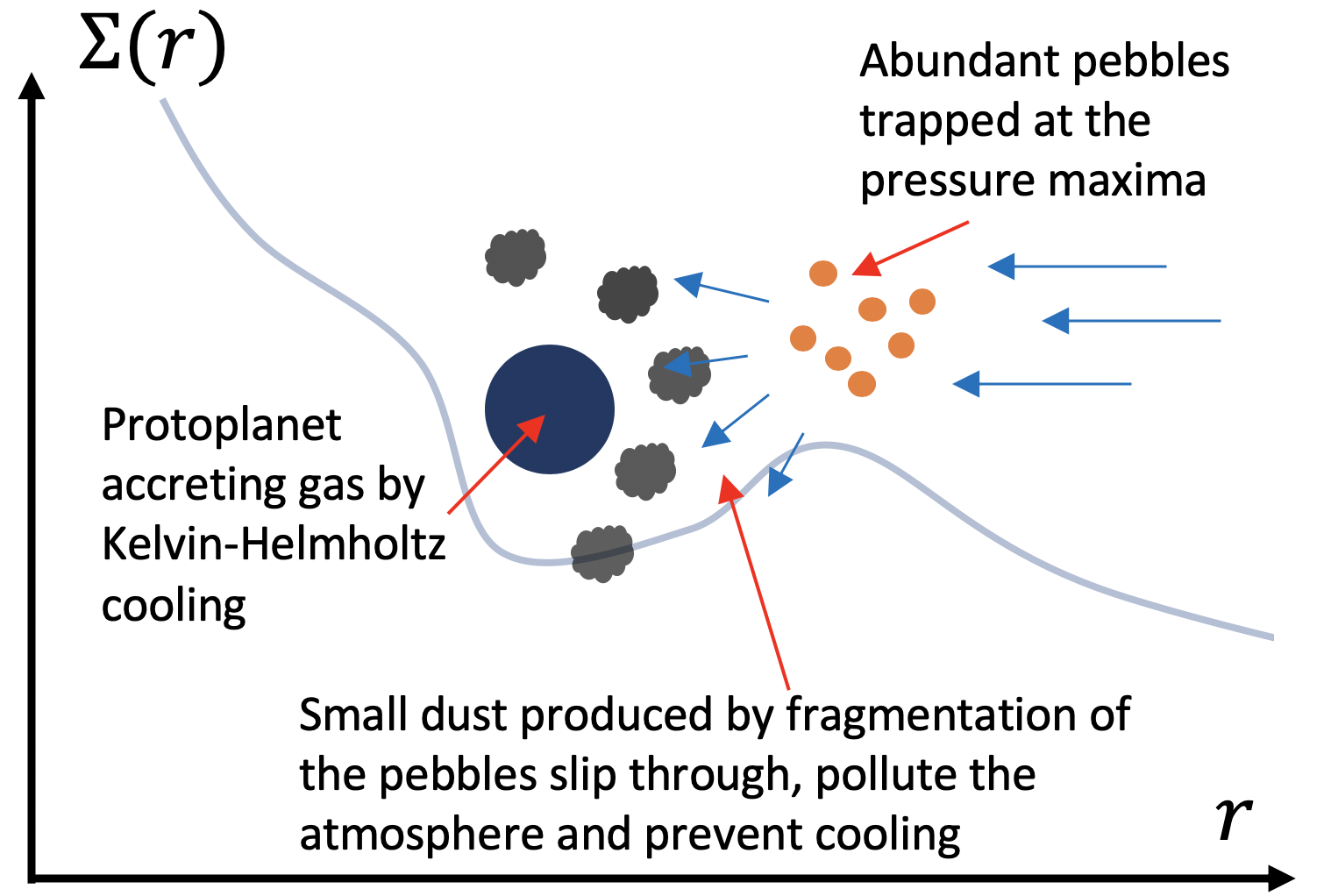

A schematic showing the main idea of the mechanism that we identified: abundant pebbles are trapped in the planet-induced pressure maxima -> a fraction of them fragments into dust and slip through the pressure barrier -> they pollute the planetary atmosphere and slows down gas accretion by elevating opacity.

Introduction

The quasi-steady core accretion phase of ~10M⊕ super-Earth cores are relatively short, which means they can easily reach runaway accretion and become gas giants within the disk lifetime (Lee et al. 2014). Possible remedies include raising the opacity/metallicity in the natal disk; entropy advection (Ormel et al. 2015); and late formation (Lee & Chiang 2016). However, the modern pebble accretion paradigm is not taken into account in these in-situ core accretion models. When the pebble reservior in the disk is sufficient, the rocky core can grow to ~10M⊕ mass and reach pebble isolation (the planet-induced pressure bump blocks in-drifting pebbles outside the planet's orbit, letting only small grains to slip through, see Lambrecht et al. 2014), and start the gas accretion process at a relatively early stage, making themselves in danger of runaway. We use numerical 2D planet-disk interaction models and 1D quasi-steady accretion models to investigate how the pebble barrier generated by the planet can change the local dust size distribution, and affect the planet's core accretion through local enhancement opacity.

Numerical Methods

We use LA-COMPASS code (Li et al. 2005) to model the pebble-isolation process of a 10M⊕ mass super-Earth core in a fiducial protoplanetary disk (PPD) model, and measure the evolution of dust size distribution (the surface density of dust in a range of size bins) at the pebble barrier and around the direct planet vicinity. The full coagulation code of LA-COMPASS model 151 dust species as different fluids, and solves their hydrodynamical equations and coagulation equations at the same time.

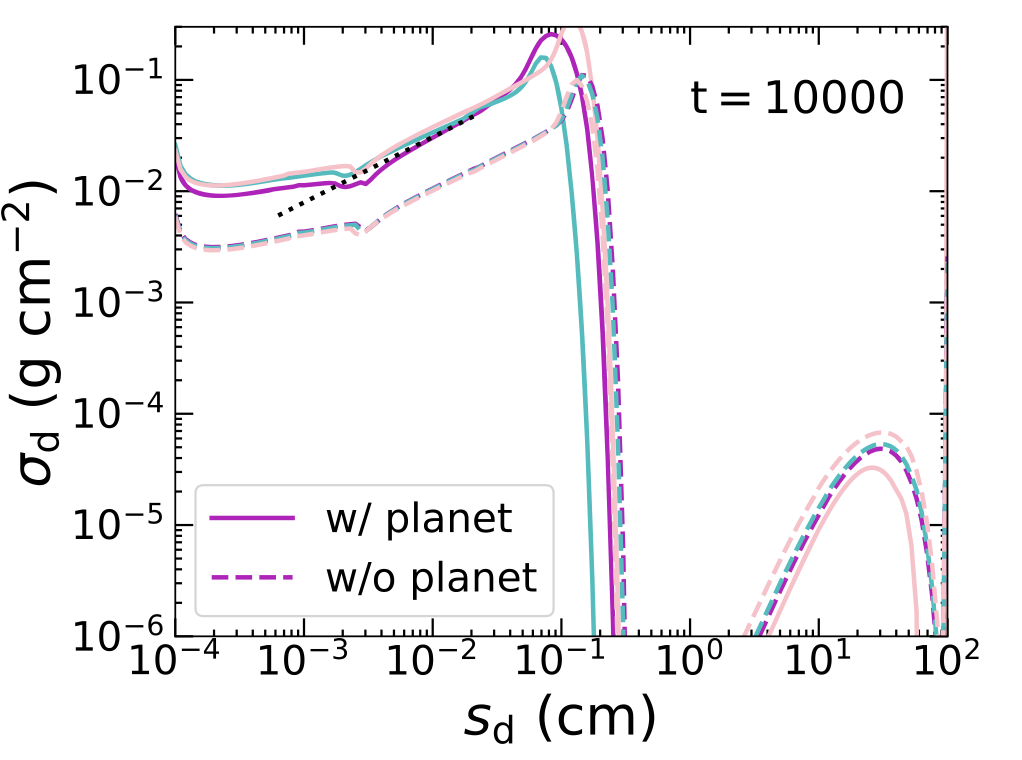

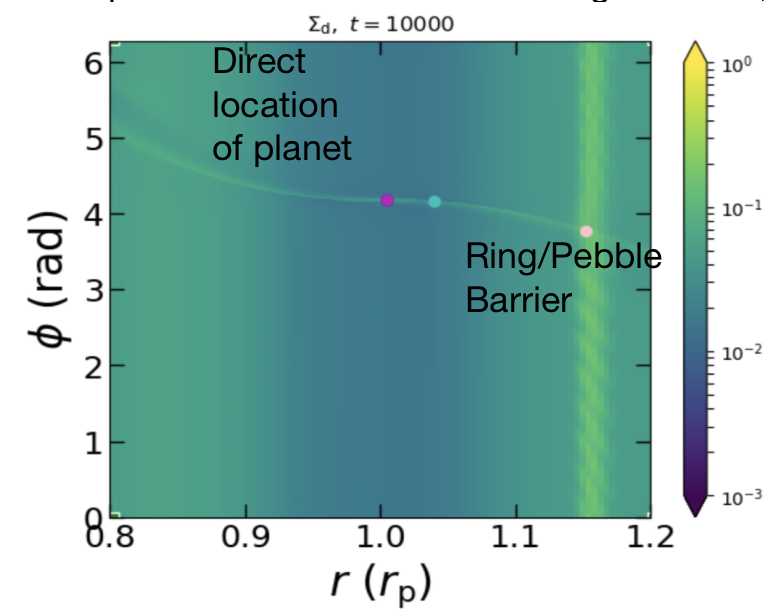

Figure 1: Dust surface density distribution inside the protoplanetary disk after 10000 orbits. Purple dot indicates the location of the planet and pink dot indicates the radius of a pebble ring at the planet-induced pressure barrier.

From the simulations, we infer two sets of dust size distributions and opacity laws for the unperturbed disk and the perturbed disk at planet location (see above figure), and use 1D atmospheric model (Piso & Youdin 2014) to numerically calculate the planet growth in the quasi-steady accretion phase. We apply the treatment of Ali-Dib et al. (2020) for entropy advection, in which an additional outer convective layer is imposed and prevents cooling.

References

Lee, E. J., Chiang, E., & Ormel, C. W. 2014, ApJ, 797, 95, ADS

Ormel, C. W., Kuiper, R., & Shi, J.-M. 2015, MNRAS, 446, 1026, ADS

Li, H., Li, S., Koller, J., et al. 2005, ApJ, 624, 2, ADS

Lee, E. J., & Chiang, E. 2016, ApJ, 817, 90, ADS

Lambrechts, M., Johansen, A., & Morbidelli, A. 2014, A&A, 572, A35,ADS

Piso, A.-M. A., & Youdin, A. N. 2014, ApJ, 786, 21,ADS

Ali-Dib, M., Cumming, A., & Lin, D. N. C. 2020, MNRAS, 494, 2440, ADS

Zhu, W., & Wu Y. 2018, AJ, 156,92, ADS

Chen, Y.-X., Li, Y.-P., Li, H., & Lin, D. N. C. 2020, ApJ, 896, 135, ADS

Chen, Y.-X., Zhang, X., Li, Y.-P., et al. Accepted by ApJ, Arxiv

Preservation of Super Earths

In the simulation of a PPD without a planet, the dust size distribution quickly becomes steady, and the opacity law inferred from the size distribution around the planet is similar to values used in previous atmospheric growth calculations (Lee et al. 2014).

However, in the perturbed case, as pebble species accumulate in the planet-induced pressure barrier outside the planet's orbit, the local fragmentation also produces more sub-mm grains that pass through the barrier, and elevates the effective dust opacity at the planet's vicinity.

Figure 2: The dust dize distribution (surface density of solids scaled with surface density of the gas) at the planet location in the unperturbed disk, and in the planet-perturbed disk. We used 151 species of dust, with their sizes logarithmically distributed in a range of 1e-4 - 1e2 cm.

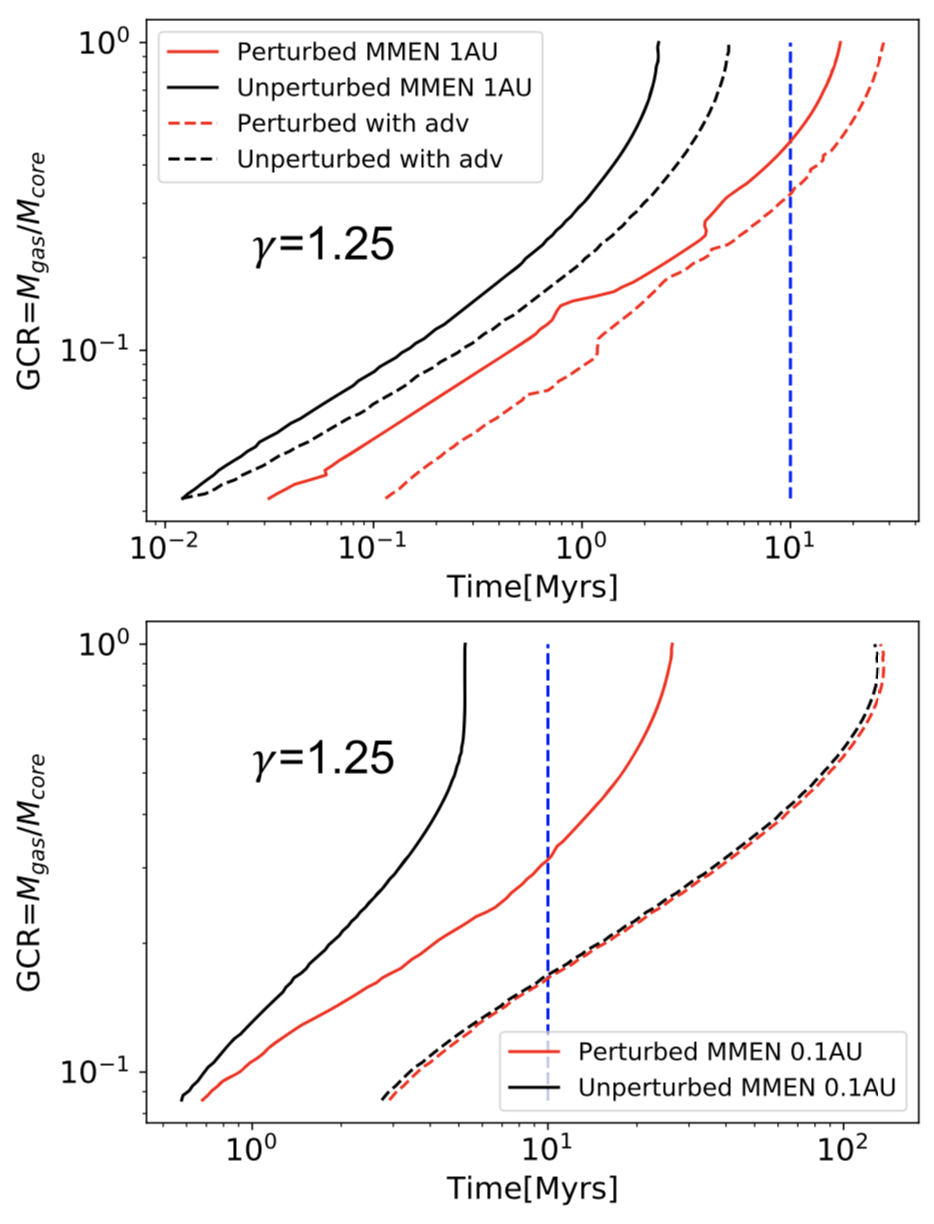

Results show that there is a ~10 time increase of the metallicity of small grains and opacity around the planet vicinity, induced by the high fragmentation rate in the pebble barrier. We find that for the Minimum Mass Extrasolar Nebula (Lee et al. 2014) disk environment at 1au, the enhancement of opacity alone (caused by pebble isolation) is able to prolong the runaway timescale by ∼10 and to prevent transition to gas giant planets. Although the inclusion of entropy advection further doubles the runaway timescale, its contribution is overshadowed by the effect of opacity enhancement.

For a super-Earth located at 0.1 au, the runaway timescale in unperturbed disk may still be less than disk lifetime, but an enhanced opacity is enough to quench runaway. Entropy advection further delays the onset of runaway accretion because the fresh external supply of entropy causes most of the outer zone to become convective. In the radiative zone the temperature is mostly above the dust sublimation limit, therefore the influence of grain opacity enhancement is quenched. In any case, the super-Earths are robustly preserved at close-in radii.

Figure 3: The gas-to-core mass ratio GCR as a function of time for a 10M⊕ super-Earth core in MMEN, for adiabatic gradient 1.25 (accounting for hydrogen dissociation). The black solid lines show growth unperturbed disk environments, and the red solid lines show growth considering the planet’s perturbation on dust size distribution. The dashed lines have taken into account entropy advection according to the method of Ali-Dib et al. (2020). The blue lines indicate the typical maximum disk lifetime of 10 Myr.

Emergence of Gas Giants

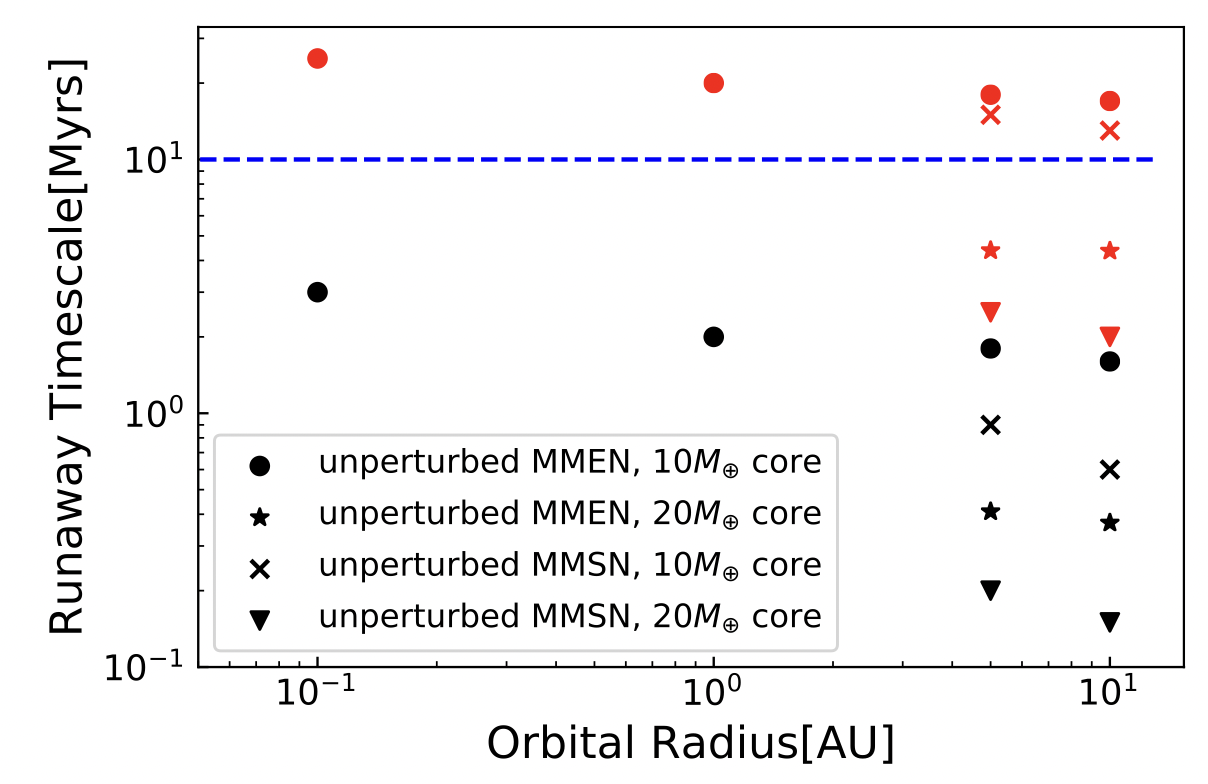

In our attempt to account for the avoidance of super-Earth’s runaway, we also find that the opacity enhancement effect seems to be in danger of quenching the emergence of gas giants. In the outer regions of MMEN, we confirm a runaway timescale of ∼2 Myr, which is insensitive to the radial distance and entropy advection. However, when grain opacity is elevated in the envelopes, the runaway timescale is still lengthened beyond the disk lifetime of 10 Myr. The same situation applies for the colder Minimum Mass Solar Nebula. However, we note that the pebble isolation mass at 5-10au can be larger than the inner regions and reach >20M⊕, and we show here that a more massive (20M⊕) core can reach runaway within 10Myrs even in a high opacity environment.

Figure 4: A summary of runaway timescales in passive disks, for different core mass and in different opacity environments. The runaway timescales for the unperturbed MMEN are insensitive to the orbital radius, as is consistent with Lee et al. (2014). The blue dashed line indicates the disk lifetime. The black symbols indicate runaway timescales for unperturbed disk environments, and the corresponding red symbols are for perturbed cases.

Conclusion

In this work, we examined whether a ∼10M⊕ progenitor core’s pebble-isolation effect can influence its own core accretion process. We carry out simulations using simple protoplanetary disk models with dust coagulation. We find that the stalled and accumulated pebbles at the pressure bump undergoes collisions to produce much smaller grains that bypass the migration barrier. The dust-to- gas ratio around the vicinity of a 10M⊕ core reaches more than 10 times the value at the same location in the case without the planet. This process significantly increases the grain opacity in the outer radiative zone of the envelope surrounding the core, which self-limits the planet’s growth rate. For 10M⊕ rocky cores even further out in passive disk regions beyond 5au, the enhanced opacity in perturbed disks is still able to prolong the accretion timescale from ∼2Myr to ∼20Myr and quench the emergence of gas giants. Nevertheless, runaway accretion can still be reached for a 20M⊕ progenitor core in a hot disk with sufficient pebble reservior, or for a smaller core in low-opacity environments if pebbles quickly drain out. Such uniform formation channels of super-Earths and gas giants helps to explain their correlated occurence rates (Zhu & Wu 2018).

Relevant Study: Type II Migration Revisited

Planet migration is another factor that endangers the preservation of planets. Specially, the Type II migration of gap-opening planets should be mitigated in order to explain for observed occurence rates of long period gas giants. In another relevant work (Chen et al. 2020b), we find that the associated gap profile of gas giants modifies the location of Lindblad resonances. In the proximity of the planet's orbit, high-order Lindblad torques are weakened by the gas depletion in the gap while low-order Lindblad torques near the gap walls preserves a large magnitude. Consequently, the surface density distribution of the disk determines delicately both pace and direction of planets' type II migration. We show that this effect might stall the inward migration of giant planets and preserve them in disk regions where the surface density is steep.